The Age of Discovery, Chapter 2: Dragons and Damsels

Day

1: 0915 hours…

Gentle

heat touches my face and hands, the kind that one instantly senses is the

warmth of sunlight. I loosen my

grip on the trestle and lift up the goggles, slowly opening my eyes. Is this the same day?

In

another moment hands are guiding me, helping me recline onto a warm, soft

surface – a bed maybe, or a couch, the padded surface warm from sunlight. My vision, though improving, is still

blurred. I can hear a voice

telling me to relax, that the process is complete, urging me to breath normally

and sleep if that is my need. I

ask about the crew, and my voice sounds strange in my ears. The other voice hesitates, speaking to

someone other than myself. “Don’t

tell him,” says the other voice.

“He’s not ready.” Then my

head settles onto a down pillow and sleep takes me.

Later,

but no idea how much so…

I

awake with a clear mind. Sitting

up I begin to take in my surroundings.

I am outdoors. There is sky

overhead and for an instant I imagine that the adventure below the streets of

Washington was nothing but phantasm.

In our nation’s capital it had been past noon. Here, the sun still lingers in the morning sky, but it seems

– somehow – both larger and more distant, a brilliant radiant round cloud. Beside me the others stir on beds of

their own. Three of the beds are

occupied, and one is empty. I

assume that someone had awakened early and stepped away, perhaps to stretch his

legs.

The

beds are arrayed upon a balcony enclosed by a well-fortified railing. The platform appears constructed of

wood, and anchored to what at first appears to be an organically-fashioned

structure of resin or amber glass.

As my vision adjusts to the physical properties of visible light at nano scale my mind begins to

comprehend. Though impossible, it

also fact: The balcony is protruding from the molted exoskeleton of an enormous

insect larva.

Dragonfly Sky-Base! Now I

understand the significance of that name, and find myself reflecting on the

common insect, whose life cycle we exploit: In the spring, dragonfly larvae

emerge from the pond, crawling up the stalks of reeds, aquatic grasses, and

cattails, attaching themselves to plants or sticks with barbed appendages,

several inches above the surface.

The insect then pupates inside the larval exoskeleton, hatching in late

summer as an adult dragonfly.

Dragonfly Base has been constructed inside one such abandoned husk. The platform where I stand at that

moment was built out from what had been the larva’s right eye.

Suddenly

the sky is filled with a multi-winged leviathan. My mind rejects what my eyes clearly identify as an adult

dragonfly. It hovers at eye level

with the platform, just out of throwing distance. My best estimate of its relative size – the creature is

easily a half-mile long! The gales from its wing-beats force me to grab the railing

with one hand while helping the nurse corpsman from blowing away. My eyes focus on the environment

that lies beyond the unfathomable insect, beyond this open-air recovery bay,

forcing my mind to accept the unalterable. Where I had only minutes ago stood six feet, three inches, I

am presently no taller than a rather small microorganism. I was almost, dare I say, nothing!

The

monstrous head of the dragonfly pivots left, then right, and in a blink, the

unbelievably monstrous animal is gone in a hurricane of its own making.

“Captain

Adler!” A corpsman shouts my name

as she appeared from a door onto the platform. She waves and hurried to meet me. “Captain Adler, I wasn’t aware that any of you had

awakened.”

“Yes,

just a few minutes ago,” I respond, “but I wasn’t the first. It looks as if Randy woke up before

me. Where did that rascal get off

to anyway?”

The

corpsman looked lost for words, and I instantly sense why. Her explanation only confirms what was

becoming clear. “I’m so sorry,

Captain. I should’ve been here

when you came out of the fugue. You see… something happened. Commander Emerson didn’t rematerialize. I mean, he didn’t come through with the

rest of you.”

“What? What are you saying – that he

glitched?” I invoke the slang term that the physicists had adopted to label the

rare phenomenon when objects mysteriously vanished during the subatomic

reduction process. Using it in

reference to the tragic loss of a crewman is crass, and I instantly regret it.

“We

telegraphed back, and their counter message confirmed it. I am so sorry.” She shakes her head while meeting my

vacant stare.

How

is this happening? I feel

empty. How could he be gone… just

like that? Randall had been a good

man, a fine officer, and the best friend I had ever had. It will not be easy to rally the crew –

not easy to get past the loss. But

we must, or more accurately, I must. “I’ll inform the crew,” I tell the corpsman, then

thank her.

Minutes

later, the crew awakens. I

gathered them and break the news about Randy. To a man, they are professional, expressing shock and

sorrow, each in his and her own way.

We craft a wreath of star-shaped pollen granules, and dedicating our forthcoming

journey to the late Commander Randall Emerson, we cast the wreath over the

railing and onto the gentle breeze of the morning convection current.

Day

1: 1045 hours…

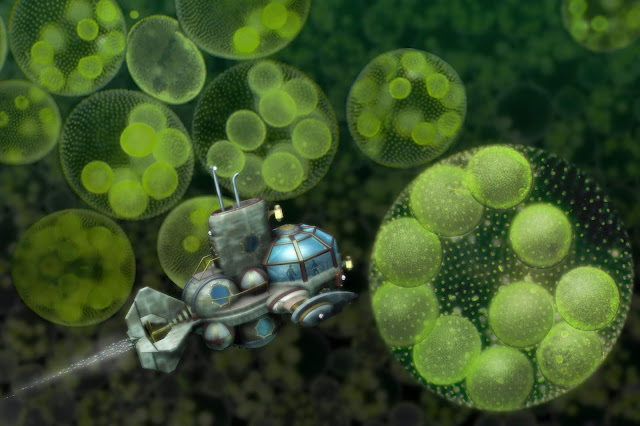

Our

transit from Dragonfly Sky-base to Duckweed Base promises to be thrilling!

Sky-base

is equipped with a number of aerial vehicles designed for reconnaissance of the

above-surface pond world, a fleet that includes hydrogen-assisted dirigibles,

and a half dozen small mechanical flyer-craft. A quartet of remarkable steam-powered ornithopters will be

used to ferry myself, and the crew, to Duckweed Base.

Each

flyer-craft carries a pilot and a single passenger, one behind the other. My pilot is a strikingly tall woman who

introduces herself as Tarah. She

explains that before joining the President’s Micro Expeditionary Corp she had

been a sailor in Trinidad, from where her family hails. Her experience with the idiosyncrasies

of Eastern Caribbean trade winds had forced her develop expert knowledge of air

currents, and the skill to harness them – a set of skills perfectly suited to

her most recent vocation. Tarah helps me into the aft seat of her flyer, makes

sure I am securely buckled in, and instructs me what to do should we have to

“bail out” – a prospect I do not care to entertain – even in my imagination.

Four

flyers are in a cue for take-off from Sky-base. Tarah and I will be the

last. As we wait our turn, Tarah

reads the morning alerts for any news of flying insects, air currents, fungal

spore clouds, or other hazards to microscopic aviation. I watch my crew, one by one, lift

almost effortlessly onto the convection breeze and vanish into the blurry

distance. When it is our turn

Tarah gives a squeeze to the Indian rubber bulb horn – AH-OOO-GAH! She pulls back on a lever to engage the

steam turbine to the drive mechanism.

Gears engage, and the wings whoosh downward. The craft lifts off the launch platform with a lurch. With a thrill of acceleration I realize

that we are airborne!

As

we clear the edge of the base Tarah puts the flyer into a gentle descent. This serves to move air faster over the

fabric-covered wings, making the ornithopter’s mechanical wing-beats more

efficient. I have never flown

before, and I find my first few moments in a flying machine to be exhilarating,

the experience perhaps enhanced by doing it at nano scale. There is no

horizon on which to focus, no detail of distant mountains to decipher, just a

haze of greens, blues, and browns.

Far

below us, the pond’s surface is a glassy plane speckled with rafts of bright

green duckweed and towering water fern, like colossal aquatic redwood

trees. The cattails at the

pond’s periphery rise like an impossibly forbidding green wall, taller than any

imagined Tower of Babylon, barely visible in the blurred distance. My mind knows that the cattails are

only a few yards away, but at micro scale that might as well be a million

miles.

Scale

was a formidable concept. We were

flying at what seemed like thousands feet of altitude, but I knew it to be

scant inches. I wondered if I

would ever overcome the habit of converting micro scale distances to macro

scale measurements.

Tarah

pulls the levers and pulleys to set the wing foils and trim the ailerons. I feel a lightness in the pit of my

stomach as we slow and began a circular descent. She levels off close to the pond’s surface, just over the

tops of the water fern.

“It’s

not far now,” she calls back to me.

A

presence, at first felt more than seen, collides with my awareness. The sensation comes from everywhere,

but is strongest from above us.

Tarah senses it, too. We

glanced skyward at the same time.

Wings, legs, eyes, a body the size of a mountain range are all coming

straight at us.

Tarah

engages the drive gears and turns hard to the left. The craft banks onto its side. I grip the holds of the open-air cockpit. The creature roars past our flyer,

nearly colliding with us. The

turbulence of its passing sends us dancing on the current like gossamer in a typhoon. The monster turns and circles to make

another lunge.

It is

a damselfly, easier to identify now that it is further away – fitting better

into my field of vision. In the

macro scale world, a delicate, beautiful flying insect, but to us, and to other

tiny flying prey, the damselfly is a terrifying airborne monster. Its mandibles snap hungrily. It will be on us in seconds. If I jump out, which I briefly consider,

I will never survive smashing into the pond’s impenetrable surface.

How

can we escape this monster? Where can

we go? I look over the sides of

the craft. An ephemeral orb,

shifting in both shape and density, catches my eye, a shadow hovering in mid

air, its form constantly shifting.

That is our salvation.

“Tarah,

down there! Look!”

Tarah

responds with action. She banks

the flyer toward the amorphous cloud… a shape whose nature becomes visible as

we draw closer to it. The cloud is

made of hundreds of individual animals, in this case… gnats.

The

damselfly pursues us. It is going

to be close.

We

plunge into the gnat cloud. The

ear-splitting dissonance of so many giant sets of wings isn’t something I am

prepared for. Tarah swerves

the flyer on a zig-zag course using all of her many skills to avoid colliding

with the tiny flies, which are each ten-times the size of our fragile flyer. With increasing hope I observe that they

are plump and well-fed, and will make a much more appealing meal than us.

I

hear the report of our success before I turn to see the damselfly devouring a

fat gnat, the victim’s clear fluids squirting over us like a sticky mist.

“That

was close,” comments Tarah.

“Remind me to have a word with the sky sentry. There was no mention of damselflies,” she says indignantly,

shaking the morning alert report in her closed fist.

Comments

Post a Comment