The Age of Discovery, Chapter 3: Duckweed Base

Day

1: 1130 hours…

We sight Duckweed Base without

further incident.

As we approach the encampment I am

struck by how many times have I looked over a small pond, or eddy along the

Potomac, and seen the brilliant green of duckweed rafts mottling the still

water. These tiny aquatic plants,

were it not for scale, looked quite similar to the more familiar lily pads –

yet a trio of duckweed leaves would fit easily on the tip of your finger.

The Micro Expeditionary Corps had

constructed Duckweed Base upon just such a trio of leaves. The base comprised a watchtower the

height of six men, a cluster of yurts, and an arrival stage identical to the

one at Dragonfly Sky-base.

Tarah banks the flyer and circles

low as she sets the wings for our landing.

I can barely feel when the skids

touch the landing stage, so expert is Tarah’s landing. I thank the pilot for her skilled

services, invoke the wish that we meet again, shake her hand, and join the crew

who are already gathered below the platform.

“Skipper!”

Lyra calls out. “Am I glad to see

you! For a minute there it looked

like you were going to be a snack for that Odonata

Zygoptera! “

“I

am delighted to report that the rumor of my demise by insect ingestion is

premature,” I respond with a smile.

“Now, where is our ship?”

“The

dock hands moved her into the water before we arrived,” reports Gyro. “It’s this way.”

Barron

grumbles disapprovingly.

“Something

wrong, Mr. Barron?” I inquire of the engine master.

“I’m

sure it will be fine,” answers the huge man in his rumbling voice, sneering

slightly. “At least, it better

be.”

Lyra

pats Barron on the arm and explains as if interpreting from another

language. “He wanted to be here

for the launch, to make sure they didn’t break anything.”

“I

should’ve been here,” mutters Barron.

“She’s a complex vessel, with a lot of sensitive systems. If any part of her was compromised

during the move I will wring the neck of…”

Gyro

laughs. “Easy, there big guy. They moved her from here to the water,

what’s that… twenty millimeters?

What could happen?”

Barron

answers sub-sonically. “Nothing…if

I had been here to make sure of it.”

“Mr.

Barron, “ I reassure him, “you may inspect the Cyclops bow to stern before we shove off. I will not ring the bell before you are satisfied that she

is in good repair. Now let’s get

aboard and make ready.”

“I

appreciate that, Skipper,” says Barron.

“Thank you.”

With

duffle bags slung over our shoulders, we cross the duckweed leaf and make for

the pier where the Cyclops awaits. A wooden walkway has been constructed,

giving us solid footing over the rough leaf surface. The duckweed leaf, despite appearing smooth to macro scale

eyes, is surprisingly rough-textured, with many dips and folds, but the raised

path makes for an easy stroll.

As we walk the crew chats excitedly about things they will miss on our

expedition, and in low tones about the amazing meals Randy Emerson would have

prepared.

Were

it not for the lack of a distinct horizon or visible geography, we could be

walking on most any boardwalk along the Chesapeake on an early summer

morning. The air smells intensely

fresh, and despite this being the season for allergies, I am enjoying a respite

from my usual hay fever. Of

course… at micro scale pollen grains are much too big to be inhaled.

We

arrive at the edge of the duckweed leaf. The mirror-like surface of the pond

extends to infinity before us.

Beneath that mirror, darkness and a universe of mystery. Moored at the end of the dock is our

ship. Cyclops is resting in still

water, a meniscus encircling her plated iron hull just below the main

deck. Through the glass panes of

her steel reinforced pilothouse I can see the outfitting crew within, stowing

provisions and removing the stays and ropes that had been used to lock down the

helm and engine controls while the ship was being moved.

The

main hatch opens. An eager

deckhand steps into the sunlight, producing a boatswain’s whistle. He puffs into the instrument and pipes

us aboard. “Welcome to Duckweed

Base, Captain Adler!” he hails. “Please find your way below and stow your

things. The Cyclops is ready to depart!”

“Oh

really? We will see about that,”

bellows Barron as he tosses his duffle into the arms of the young sailor.

Day

1: 1150 hours…

As

it turns out, Barron can find no fault with the ground crew charged with moving

the Cyclops. He reports her mechanical condition to

be “shipshape,” although I suspect he is disappointed that he has no further

justification to disparage the outfitting team.

I,

too, personally inspect every compartment, passageway, and cabin. It is, after all, my first time on

board since her completion.

My first visit to see her was when she was under construction in a

secret Maryland shipyard, an iron skeleton with unfinished decks, no glass where

her portholes and observation panes would eventually be, her brass fittings yet

to be installed. Even though I had

studied the plans judiciously, and knew the ship quite well from a theoretical

perspective, it is something else to actually touch her hatches and bulkheads,

smell the oil of her freshly varnished decks, hear the groaning of her iron

hull warming in the midday contentedly, and admire her gleaming bright-work.

I

complete my inspection back on the command deck, draw out my watch and check

the time. It is three minutes to

noon. I thank the harbor chief and

shake his hand. When the last of

the dock team has disembarked, I call all hands to the pilothouse.

“Fellow

explorers,” I begin, “today we set forth on an enterprise of scientific

discovery. Do we fear the unknown? By some measure, perhaps – but we seek to

dispel the unknown with the known, with observable, the factual, for scientific

fact is our ally. Facts are

powerful for overcoming fear, and apprehension. Discovery of fact is our mission. This ship and our commitment to her mission will allow us to

enter a world that until now has lain hidden under humanity’s very nose. We do not do this to lay claim to new

lands, or plant our flag on untouched shores, for the micro universe belongs to

no nation. What we discover will

challenge ideas once held as doctrine. The mechanics of life will no longer be subject to

guessing. We will be the first

humans to actually see life’s fundamental processes, to gain new understanding

of how those processes are carried out by all of Earth’s organisms, not just

the simplest. We will discover

forms of life that we cannot yet imagine, be it animal, plant, or neither. We enter this new world knowing that

the record of our observations will fundamentally change how humankind looks at

the world, and how it views itself in both the eternal, and the

infinitesimal. May the wind

be at our backs, the currents in our favor, and may the Cyclops keep us safe, and bring us home. Now… if you please, all hands to stations.”

Day 1: Noon...

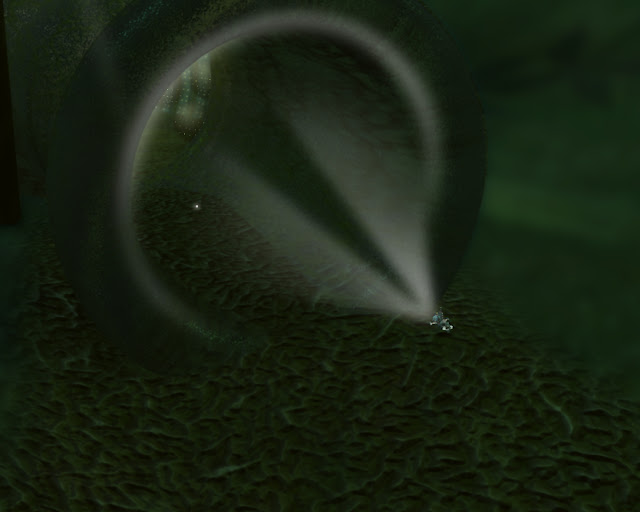

With a cheerful

ringing of the ship’s bell we depart Duckweed Base. Through the encircling glass of the pilothouse observation

dome I watch the dock hands cast away mooring lines. I give Gyro the command to

take us sub-surface. The interface

of air and water rises up and over us effortlessly. Water closes over the ship without the slightest turbulence,

its normal adhesive properties neutralized by a hull-coating of thinned oil,

without which the surface tension of air-meets-water would be an inescapable

trap.

Pre-mission reports echo in my mind, warnings about the more obvious

hazards we can expect to encounter near the surface. Hopefully we are too small to be of any interest to the

large vertebrates (fish and frogs) that inhabit the shallows near Duckweed

Base.

We drift forward and down.

The crew stares silently outward, captivated by the upper most veneer of

this new world, a layer of visible motion caused by a great multitude of

microorganisms. The teacher in me

is difficult to stifle, but I resist the urge to give instruction, or to point

out objects d’ intérêt.

The underside of

the duckweed raft is a hanging jungle of hair-like rootlets, to us the size of

tree trunks. The rootlets are home

to a teeming and diverse throng of microbes. Most visible is a species that

extends itself out into the water by means of cord-like stalks. At the end of their stalks, the

organisms circulate water into mouth-like openings, filtering out the edible

specks, which are themselves even smaller, simpler organisms.

Lyra is pressed

to the glass of the observation dome, her German-fashioned binoculars trained

on the nearby organisms. At random

intervals she lowers the glasses to scribe a brief note. My desire to linger here and document

this first encounter with single-celled organisms is powerful, but the open water

of the pond universe beckons, and the field survey schedule rigid.

“They are

amazing,” I comment, breaking the silence. “Lyra, you will no doubt be pleased to learn that I intend

to dedicate more observation time to this species later, but we must move

on. Gyro, please set a coarse for

the open water, and signal the engine master full steam.”

From his station

at the magnificent brass and wooden wheel Gyro informs me that it will be early

tomorrow before we reach our first survey site. At his right hand, the sound of the engine order telegraph

acknowledges full speed.

As we leave the

duckweed rootlet micro habitat in our wake, Lyra cries out. “Skipper! This is fascinating!

Those stalked cells reacted en

mass! Their stalks are

spring-loaded!“

I look astern at

the curious microorganisms. They

had indeed withdrawn, their stalks now coiled tight so that the organisms were

pulled into a tight bundle. “A

defense mechanism?” I ponder.

“Very likely,”

confirms Lyra. “But I’m wondering

what triggered it. The organisms

may have sensed our wake.”

“Maybe,” chimes

in Gyro, “but it has me concerned.

It might be a good idea for Lyra to take a look around the ship with

those fancy binocular specs of hers, and make sure we’re not alone out here.”

Several minutes

later Lyra returns to the pilothouse, reporting that she has visually scaned

the waters surrounding Cyclops, and

had found no cause for alarm.

We steam on for

several more hours. Twice in that

time Gyro reports a momentary vibration at the wheel, as if something large

passed astern, sending a pressure wake over the ship’s rudder. But nothing further comes of it. As the waters around us grow dark, I

order all stop for the night. Barron deploys our sea anchor and we take

turns on watch.

Day 2: 0530 hours...

After a welcome night’s rest, we

greet the sun’s first rays with hot coffee and high hopes for a productive

day.

Lyra observes a vertical migration

of nearby algal plankton, green single-celled organisms, moving toward the

surface. She theorizes that

like plants, the green cells require sunlight to power their life

processes. Sunlight diffuses

rapidly through even scant centimeters of water, so the organisms must have the

means to detect light levels, and to move closer to the more intense light near

the surface. This is our first

encounter with plant-like organisms that had the power of locomotion.

730 hours…

We arrive at the region of the pond

designated on our charts as the open water.

This region is by far the largest of the pond habitats, and is home to a

huge diversity of micro animals and single-celled organisms. All together they are called plankton. Some of these organisms are predators, but most are prey for

the predators. As with the

ecosystems of the macro scale world, prey out-number predators many times

over.

As the morning light increases we observe

untold thousands of the green single cells of many different species

congregating near the surface. As

the day progresses and the light intensity increases the green plankton

reverses its vertical migration, moving downward away from the surface and away

from the light. Lyra theorizes

that this behavior serves to protect the organisms from becoming overheated,

and from other possible sun-related hazards.

Shortly before eight bells Gyro

calls on the voice pipe, summoning us to the pilothouse. In the near distance, eighty

millimeters perhaps, a much larger creature has arrived. It is red and distinctly

lobsteresque. Referencing one of

her field manuals, Lyra identifies the animal, as suspected, a member of the

crustacean family – most likely a species of copepod – very tiny relatives of

shrimp and crabs. This copepod has

placed itself in the middle of a green cell migration. With an excellent opportunity to

observe a predator-and-prey relationship we hold position and watch with

fascination as the crustacean, five millimeters long at least, enjoys a boundless

feast. The copepod creates a

maelstrom with an assemblage of swirling hairs, and draws the helpless

single-celled green organisms into its grinding jaws.

“That feeding vortex is powerful,”

observes Lyra. “It’s pulling in

food organisms of all sizes.”

“And munching every one of them,”

comments Gyro. “The glutton!”

“I don’t think so,” says Barron,

chiming in. “It’s actually rather

picky. If you look closely, the

copepod only swallows small stuff like those green algae cells, of which there

are thousands. But look what it

does when a larger object gets caught in the vortex. There, see! It pauses its vortex-makers. The current

stops for a moment and it rejects anything that’s too big too eat.”

“A picky glutton,” adds Gyro.

That’s when the deck tilts suddenly

under my feet and the railing surrounding the command deck meets abruptly with

the right side of my head. For a

moment everything goes black and alarm bells echo in my ears.

Comments

Post a Comment