The Age of Discovery, Chapter 15: Lights, Camera ... Action!

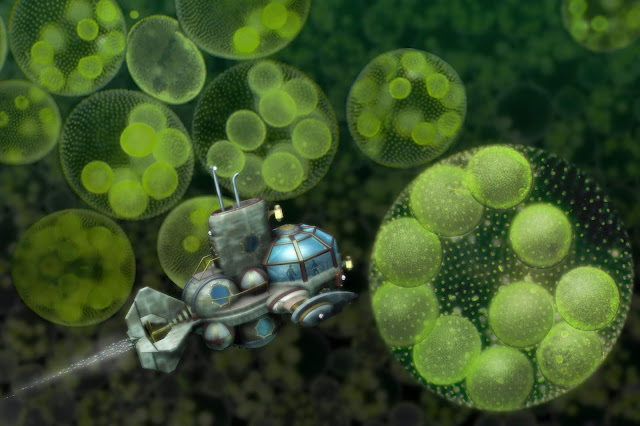

The celluloid is rolling! We are

now several days into the production of a moving picture documentary. When complete,

our film will feature the numerous kinds of microscopic organisms found

throughout the pond.

The recent acquisition of several

oxygen-producing algal protists has extended how long we can remain submerged,

allowing for lengthier observations… and more time to “get the shot,” as they

say.

We are currently navigating our way

through the dense and occasionally treacherous weedy shallows – treacherous

because navigation is more hazardous, and one never knows what micro-denizens

may lurk in the shadows of this aquatic jungle.

Because of the abundant aquatic

plant life for shelter, and plentiful sunlight, this region offers safe haven

for a rich diversity of microorganisms. Again and again we see, whilst filming, the relationship

between hunter organisms – and organisms that graze. The hunters, or predators,

capture and devour the grazers, in much the way the lion feeds on the wildebeest.

The grazers, or prey, do not hunt.

Most are green photosynthesizers that make their living harvesting energy from

sunlight. And those that do not

use photosynthesis as their mainstay glean decomposer bacteria from rotting leaves

and decaying micro animals. This “weedy

shallows” region of the pond is an ideal biome for studying the relatively new

science of ecology, a measured discipline that examines how predators, prey,

and the environment interact, and are interdependent.

Day 13: 0730 hours...

We are now deep into these weedy

shallows. Lyra has

enthusiastically embraced the photographic survey of our voyage, and these past

few days can often be found behind the camera. As the ship steams at meager docking speed, the surrounding jungle

moves slowly by. All hands are

quiet, content to observe the richness of life streaming past the ship, with

something akin to awe, and even reverence. The only sound for several minutes is the whir of film

moving past the shutter of our prototype British Aeroscope motion picture

camera.

“I can’t wait to begin editing,”

whispers Lyra, her eye pressed to the eyepiece of the camera. “This documentary, which I’m thinking of titling ‘Life in a

Freshwater Pond: As Seen Through the Eye of the Cyclops’ will change the world,

or at least how people see it! It

will reveal that the micro world is a living dance of predators and prey, of

survival at any cost.”

“I like the title,” said Gyro, then

cleared his throat and intoned what I had already been thinking. “Let us hope

that we finish it before becoming prey ourselves!”

1030 hours...

We are encountering so many new

organisms that the camera is rolling constantly! We spy a type of algae made up

of cells that connect to each other end-to-end, creating extremely long

strands, like hair. The green chloroplast in these cells is spiral shaped,

which likely allows it to receive sunlight for photosynthesis no matter where

the strand is drifting in relation to the sun. I look over Lyra’s shoulder to see what she has just

scribbled on her filming notes: the word Spirogyra.

Nearby we photograph a busy cluster

of spherical green colonies. The individual green cells have two flagella each,

similar to the species that we now tend aboard ship for oxygen production. These spheres are able to keep their

small colony of sixteen cells facing the sun for efficient photosynthesis.

And then a big surprise – a

ciliated microorganism that walks! This beasty patrols stems and branches of

pond plants, hunting algae. Its legs appear to be specialized cilia that are

fused into limbs, and more cilia that create a feeding vortex.

1215 hours...

Diatoms surround us! It’s hard to believe that just a few

days ago we had to move heaven and earth to get enough oil from these

glass-encased algae cells to resume our voyage.

Diatom glass, like all glass, is

made of silica. I cannot help but wonder where might the diatoms extract silica

for making their glass houses? Equally as fascinating as its glass enclosure is

how a diatom buoys itself to hold position at the best depth for photosynthesis;

it does so by producing those lighter-than-water oil droplets. And oil, we know, is very high in

carbon. From where, we wonder, do they get the carbon – and how might they

synthesize oil from it?

Some time back we discovered many uses for diatom

products. Aboard the Cyclops we repair windows and portholes with

glass harvested from diatoms. We use the oil droplets for fuel and machinery…

and as a surfactant when necessary to negate surface tension. In the weedy aquatic jungle there is a

thriving variety of the class diatomatae,

some green, and some yellow – but I must tell you that the chloroplasts from

all varieties of diatoms make a delicious salad!

1330 hours...

It is fortunate that we are filming

this abundance of Kingdom Protista,

because memory alone could never serve as adequate record of our

observations. Life, and movement,

is everywhere we direct the camera. But how do these free-living single-cell

organisms move about? Our film has revealed that all independently living cells

fall into one of three groups, generally based on how they get about.

The Amoeboids: Amoebas and their

relatives move by extending blob-like appendages that flow like living putty.

The Flagellates: A long whip-like

strand, or bundle of strands, wave rapidly, pulling the cell through the water

like a propeller.

The Ciliates: These cells are usually

covered in a coat of small hairs that move wave-like, in any direction, to move

the cell. Ciliatea is the most

diverse Class of Kingdom Protista.

Some have cilia adapted for walking, others for feeding.

Ciliates are the speedsters of the

microscopic world, and most are much faster than the Cyclops at full-steam!

1420 hours…

SPROING!

We’ve just now observed a most

amazing ciliate that tethers itself by way of a spring-loaded stalk! This is the very same protozoan we

observed thriving among the aquatic rootlets beneath Duckweed Base, at the

beginning of our historic voyage. I

have been eager for the opportunity to study this fascinating genus more

closely, and my chance has finally arrived.

When a disruption, such as a

predator comes near, the cell instantly retracts the stalk, affectively jerking

itself quite suddenly out of harm’s way. After a time the stalk relaxes and

extends. With danger no longer

present, the cell resumes feeding – a process of drawing in small algae and

bacteria that become caught in its whirlpool-like feeding vortex.

“It is the Bell Animalcule,” proclaimed my young naturalist from behind the

camera, “but today they are known as Vorticella.” From the safety of the observation

deck, she has been filming a colony of these stalked protozoa for several

minutes. “They were first observed

by the inventor of the light microscope, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, in 1676,”

Lyra proudly recites, “and were later named by...” but before she can grace us with more fact-filled biology

history she gasps and focuses her lens on a new development outside – we have

been blessed by fortune to catch one of the vorticellids in the act of

reproducing!

“You say it’s doing wha…what?” asks

a blushing Gyro.

“I can’t believe our luck!”

proclaims Lyra. “They reproduce by

fission,” she continues to wax while filming. “And just like most protozoa we’ve encountered, prior to

cell-division the organism divvies up its internal organelles, then pulls

itself into two new individuals!”

“Is that what they do instead of…?”

ponders Gyro aloud, stopping himself mid-thought.

“Instead of sex?” asks Lyra,

completing the steersman’s inquiring thought. “Actually, yes it is.

All protists are genderless.

The exchange of genetic material is not required. After fission each new cell is

identical in every way – and look, they are about to separate! One of the new

vorticellids keeps the spring-loaded stalk. The other one swims away, using its feeding cilia for

locomotion. Presumably it finds an

anchoring site and grows a new stalk of its own.”

All hands are intently observing

the newly anchored daughter cell and the crowded cluster of adjacent

vorticella, when without warning every individual retracts lightning-fast on

its stalk.

“What happened?” shouts a startled

Gyro.

“Something triggered their

danger-avoidance response,” answers Lyra, as a shadow passes over the brightly

lit vorticella colony.

And suddenly, I am struck with a

foreboding sense that our own demise may be at hand.

*****

Author's note: Microscopic Monsters is now being featured on Best Science Fiction Blogs

Comments

Post a Comment