The Age of Discovery, Chapter 9: A Gift of Diatoms

Day 8: 1415 hours…

Diatoms, Lyra informs me, are a very common and successful alga, and I am

glad to hear it. The sooner we

begin harvesting them for their oil, the sooner we will be out of danger. Lyra continues her diatomaceous

diatribe, revealing that this family of algae has been on Earth approximately

two hundred million years. It is

adapted to fresh and saltwater environments, and is most noted for the houses

of glass that enclose each single-celled individual. Diatoms thrive in the sunlit water just beneath the surface,

where conditions are ideal for photosynthesis and nutrient absorption. Lyra suggests that we would likely find

all the diatoms we need clinging to the stems of aquatic reeds and

grasses.

“Sounds like we have a classic paradox,” announces Barron. “The oil we need to break the surface

tension is with the diatoms… below the surface that we can’t penetrate without

the oil.”

“I have a thought about that,” muses Lyra. “One of those pond rushes

could be the solution to our way down.

If we cut a hole through the epidermal cell layer, then crawl through,

we should have access to any number of vallecular canals – vertical shafts if

you will – giving us an unimpeded descent down through the stalk. We descend about a centimeter, cut

another hole back out through the epidermis, and start pulling in as many

diatoms as we need.”

“A sound plan,” I add. “But

if possible, let’s try to extract the oil without mortally wounding the

organisms.”

“But skipper,” complains Barron, “that will slow us down. These are just diatoms. Wouldn’t it more efficient to bring

them up and, well…process them on the surface?”

I appreciate Barron’s use of polite vocabulary. He is correct.

It would be faster and more efficient to leverage open the cells’ glass

cases, tear open their cell membranes, and collect the oil globules within. These microscopic organisms are plentiful…

ubiquitous even. They are no more

complex than a single cell in a blade of grass. Sacrificing a dozen won’t have the slightest effect on the

local micro-habitat. But it is a waste, and I have to admit that my own

microscopic condition has altered my perspective. Are my crew and I any more important, or more valuable, than

these denizens at the bottom of the food chain? I’ve made my decision.

“While we don’t know what happened with the algal protist in our lab, I’m

not going to risk another incident.

We will carefully extract the oil from the diatoms without seriously

harming them.”

“So be it,” adds Barron compliantly. “I’ll set up a rope and pulley. It will make dropping down

through the stalk and getting back up much easier. And on the return trip we will have the oil to carry as

well.”

I watch with pride as my crew dives

into the task. A short hike from

the stranded Cyclops Lyra find a

suitable rush protruding up from the glassy surface. She circles it quickly and returns to us with a look of

surprise. “You’ve got to see something,”

she says mysteriously. “Follow

me.”

Lyra leads us around the huge green

trunk of the rush stalk. It rises

up to meet the sky, vanishing indistinctly where its tip becomes lost in the

blue dome of celestial blur. The

stalk’s skin is rough with a waxen cuticle that covers thousands of brick-work

like plant cells about the size of barrels – to us. I run my fingers over the cuticle layer as we circumnavigate

the rush. Spines the length of my

arm protrude out from the fibrous covering at random intervals, which likely

served to make it unpleasant as a food source for small pond arthropods.

As we round the backside of the

stalk Lyra halts, indicating a section of the green wall with her outstretched

hand. “Have a look at this.”

It is a doorway.

A rectangular opening has been cut

into the stalk, just about knee height above the smooth water surface. In shape and proportion, the opening is

uncannily ideal for micro-scale humans.

“The cuts that made this entrance

look fresh,” reports Barron as he inspects the doorway. “And you may not like hearing this, but

the work is too precise to have occurred naturally.”

So obvious is the truth of Barron’s

statement, that it hangs ominously in the air, and none of us can reason a

proper response.

Finally, Lyra, running a hand along

the deep incision, invokes professional analysis: “A hole this small would normally heal over in minutes, but

the opening has been treated with a metabolic retarding agent to keep it from

closing back up, probably a hormonal growth inhibitor.”

“But left open for what reason,”

asks Barron. Then voicing what

Lyra and I are thinking, he continues. “Whoever made this opening wanted it to

stay open. Did they do it for

us? Or do they have their own

reasons for going inside a pond rush?”

Time is short, and my skipper’s

intuition senses no peril. Barron and Lyra are looking at me, awaiting a risk

assessment and a decision. “We are facing a matter of survival. We have to retrieve the oil from the

diatoms and get the ship back in the water. Whether this opening is natural, or made for some other

purpose seems irrelevant at the moment.

We have an easy way inside and we’re going to use it.”

1440 hours…

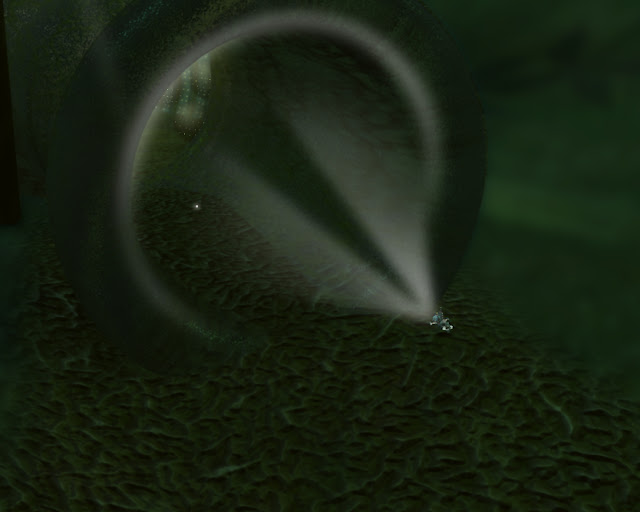

Over the opening Barron has assembled

a block-and-tackle rigged with hemp lines dangling down into the greenish dark

of the rush’s inner shaft. He

fashioned a pair of flat horizontal seats for Lyra and I, then began lowering

us down that vertical tube, slow and steady. A third seat conveys cutting tools, dive suits, and a small

quantity of olive oil. Saw and

chisels will allow us to cut our way through the outer wall of the rush, and

the dive suits and olive oil will let us slip through the air/water interface

to collect diatoms for rapid oil extraction.

Lyra and Barron have invented a

solution for collecting the oil from the algal cells both simple and

inspired. Without harming the organisms,

we will insert an arm-length section of microtubule through a pore in the

cell’s glass case and exploit the physics of capillary action, wicking the oil

out. The oil globules will then

rise to the surface on their own, where Barron will collect them for transport

back to the stranded Cyclops.

The descent through the interior of

the enormous pond plant is an almost serene experience. It is as if being inside a huge

cathedral, illuminated from all sides by endless stained glass columns of repeating

geometry. Such precise orderliness

can only be found in the exacting replications of biological processes. Cell after identical cell, without end,

forms a breathtaking biochemical latticework. Occasionally a shadow rises beyond the cellular tapestry –

cast by a midge pupa rising up from the bottom – a sober reminder that our ship

and our mission are still in peril.

The luminous green hues of filtered

sunlight from the surrounding plant tissue become incrementally dimmer as we are

lowered further and further down the vallecular canal. When roughly ten minutes elapse, we

arrive at our destination. It

seems that our arrival has been anticipated.

Our feet come to rest on a solid

surface – a platform made of cellulose planks of meticulous craftsmanship. The floor fills the shaft wall to

wall. A doorway, similar to the

one on the surface, is cut into the outer wall of the rush, but unlike the one

above, this one has already healed over, leaving only a door-shaped patch of

scarring and fresh cuticle. But we

won’t be needing the door for recovering diatoms this day, for the work had

already been done: glass cylinders, three-dozen in total, each filled with

amber tinted diatom oil – stacked with precision beside the healed-over

doorway.

Lyra whispers: “This isn’t possible. Am I imagining this?”

“Oh it’s real, but I am at loss to

explain it,” I muse. “And while

every possible explanation is mind boggling, one thing is clear… this cannot be

a natural phenomenon.”

I can hear Lyra forcing back

laughter. “Oh, you think? The only thing missing is a red ribbon

on top.”

“And that is precisely the

question: is this a gift, or an invitation to be gone,” I counter.

Lyra lifts the fitted glass lid

from one of the cylinders. She

dips a finger into the oil inside, rubs it between her thumb and forefinger,

works it into the skin of her knuckles with a pleasurable sigh. “It’s pure. It’s perfect.

Jonathan… who did this?”

“Who, or what.” I am trying to control my racing mind

and its wild theories.

“Jonathan,” Lyra begins carefully,

“do you suppose whoever did this – or whatever – is the same thing that came

aboard the ship and removed the remains of that algal protist?”

Of course I was considering this

very possibility, a likelihood that had been foremost on my mind since

discovering the doorway into the rush.

If I accepted as truth that something had come aboard my ship and taken

away the dead protist for reasons as yet unimagined, it was no leap at all to

believe that the same intelligence was at work here as well. Had this mysterious party foreseen our

need for a surfactant, and made it available? But why? Did they reason that helping us was a

way to spare the lives of the diatoms it believed we would slaughter? Based on our prior handling of pond

life, it could not have known that our intention was to extract the oil without

harming the organisms. Were I to

invoke the rigors of the scientific process I would conclude that my

imagination was getting the better of me.

“That is a tempting deduction …” I

muse, “but there is insufficient evidence to connect the two events. Scientific discipline holds that

we acquire more data before we embrace such a conspiratorial concept.”

Lyra assessed the canisters, their

flawless construction, their perfect orderliness. “I think the most powerful evidence is sitting right in

front of us. This diatom oil… it’s

the exact quantity, down to the last canister, that we need to get the Cyclops back in the water. Whomever did this had to make a precise

calculation…”

“Or has comparable insight or

behavior.” I am reflecting on the

animal world, on how a Pacific salmon knows the very stream where it emerged

from the egg, then stores just the right amount of fat to fuel a one-time

upstream swim up that very stream for its final act of life. Or Monarch butterflies, that migrate

thousands of miles every year to the same groves in California and Mexico, to

escape the deadly chill of winter.

Or herds that follow the east African monsoons….

My ruminations were interrupted

with the unannounced sideways lurch of the chamber. The rush is swaying.

“It’s a wave!” announces Lyra.

“Probably just a ripple,” I reason. “A frog probably jumped in. Hang on!”

We lean into the tilt of the room,

grab onto the loose ends of microfibers that formed a furry covering on the

inner wall of the plant’s shaft.

Lyra lifts a concerned face. “I hope

they’re okay up there.”

As the wave passes and the floor level

and solid once again, my thoughts go to our fellow shipmates. I know that Barron and Gyro are well-trained,

and that each man has the requisite skills to survive in this world, even if,

perish the thought, the Cyclops were

scuttled.

A massive shadow swallows the gentle

filtered light that we have enjoyed in this verdant sanctuary. The wave has awakened something. An ear-splitting scraping sound

accompanies the silhouette of some monstrous arthropod crawling up the outside

of the rush. Three body sections are

unmistakable through the green walls of the plant’s inner shaft – an

insect! Its many legs move in

slow, mechanical fashion, as it scratches and claws its way toward the surface. Then the light returns and the insect

gone.

Lyra and I quickly load as many of

the oil containers onto Barron’s elevator sling, about half the total

number. Getting them all to the

surface will take two trips up the vallecular canal. To signal Barron we are ready, I give the line three short

tugs. I wait. I wait too long. There is no response, no slow ascension

of the sling, no counter-tug of acknowledgment. I try again, with greater force. And still, no sign from above that Barron received the

signal. We are stranded.

Comments

Post a Comment