The Age of Discovery, Chapter 18: The Bottom Ooze

Day 14: 1100 hours...

Crisis!

I am loath to report that we are stranded, now mired to the gunwales in

the bottom ooze – and I have only myself to blame.

The accident occurred in the middle of a strategizing meeting with

naturalist Lyra Saunders and engine master Barron Wolfe. They were elucidating me on their

well-reasoned plan to modify Cyclops’

fuel production by utilizing the product and by-product of photosynthesis

(starches and oxygen, respectively) to fashion a fuel supply that would be

emission-free, resulting in no carbon exhaust, making us undetectable to the

predators of the pond micro verse.

As proposed, our menagerie of green algae cells, which has provided the

bulwark of our oxygen production, could also be utilized as a starch farm. The starch would be processed to make a

clean fuel for the boiler.

Combustion would provide heat to drive the turbine, and the carbon gas

waste product channeled back to the algae cells, that with the addition of

sunlight, would continue the cycle.

The idea was nearly perfect… the single stumbling block being that we

had yet to discover how to easily convert the starch, which was itself

combustible, to a higher energy-yielding fuel.

We were, in fact, discussing this very issue when there came a loud

report, a metallic ‘BANG’ from aft.

The interruption hung for a moment in the cabin air as we looked at each

other with a range of expressions, puzzled to concerned.

“Skipper, better get up here…” came Gyro’s stern declaration over the

voice pipe.

Barron was bound for the engine room without a word. I raced for the wheelhouse, Lyra at my

heels. In that moment I knew I had been remiss: following our run-in with the

planarian, and more recently with the hydra – both of which were taxing to the

ship’s constitution – I should have ordered a stem-to-stern inspection. But I neglected to do so, caught up in

the excitement of new discoveries, and now some important piece of equipment

had failed.

We charged into the pilothouse, found Gyro clutching the ship’s varnished

oaken wheel with his left hand, his right pulling futilely on the elevator

control lever.

“Control cable snapped,” he shouted in a matter-of-fact greeting. “She won’t pull up!”

Yes, I thought with alarm and self-recrimination, something so obvious

would have appeared plain as day in a cursory inspection… if only I had ordered

one.

The following moments are a blur… of alarm bells… of desperation to

regain control… of the pond bottom rising up from the shadowy depths as Cyclops plummeted deeper and deeper.

“Hang on!” shouted Lyra, but her warning was unnecessary. My knuckles, bone white, were locked

around the safety railing in an iron grip. Around us, water roared past the observation panes with the

sound of a hurricane. Ahead, the

terminus of our steeply sloped path loomed with ever-increasing detail.

And then we met with the bottom.

Iron howled, steel screamed, wood trembled. Cyclops’ downward

momentum was turned into forward motion in an instant, and the change in

direction threw me over the railing and into a forward pylon separating two

glass panels. I lay on the deck,

looking up at the glass panes through which a dense cloud of bottom detritus

was roiling around the ship – but to my surprise, no collision came then – or

ever.

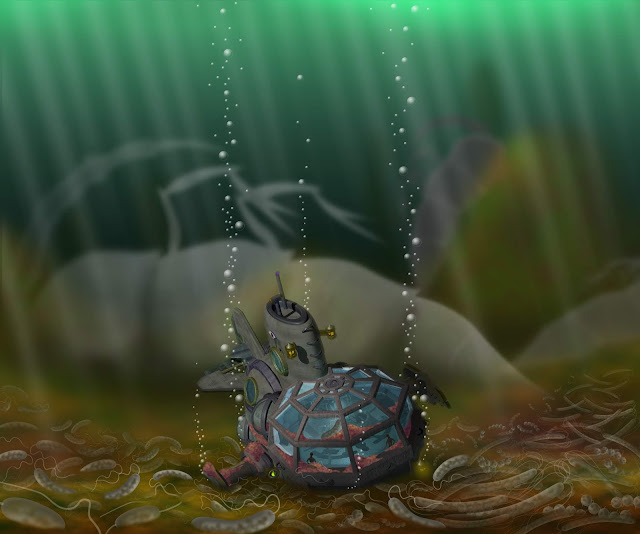

The bottom, it turned out, was soft as goose down. Cyclops

came to rest on a vast pillow of spongy ooze

– the term given to the bottom micro habitat: a layer made up of dead plants

and animals that rained down from the upper levels of the pond, home to the

tireless decomposer organisms that constantly converted organic matter back

into basic molecules for re-entry into the food chain.

As the cloudy water cleared from around the stranded ship, our immediate

surroundings became perceptible in the murky light. The motionless silhouettes of hulking dead micro crustaceans

littered the bottom-scape to the edge of visibility, like monstrous prehistoric

invertebrates transformed into mountains.

Periodically the body of a Daphnia, or copepod, would drift down from

above, and settle amongst the carcass-littered bottom with a small puff of

cloudy detritus.

1330 hours...

“Jonathan, this is interesting,” says Lyra from where she

tends the environmental sampling station in our laboratory. “The water down here is much lower in

oxygen than near the surface. And the carbon dioxide levels much higher.”

“That is indeed curious,” I say in

agreement. “I hope that we have an

opportunity to discover what might account for such conditions.”

Lyra begrudgingly accepts my clumsy

change-of-subject, and turns to greet Gyro and Barron.

The crew and I have gathered in the

lower deck laboratory to assess our situation. We are in one piece, thankfully – more a tribute to Cyclops’ stalwart construction, than any

clever action taken by her skipper.

We have survived our ungraceful landing with only minor structural

damage. To avoid another oversight

like the one that now finds us stranded on the pond bottom, I have ordered

ship-wide inspections of all mechanical systems.

Engine master Barron has already

begun repairs on the severed elevator control cable that put us here, and as he

enters the lab, reports that repairs will be complete in half a day. But a larger problem looms: a storage

tank was ruptured in the crash and the last of our fuel oil is all but gone.

“And in summation, we have just

enough fuel to spin the dynamo and keep the lights on,” explains Barron,

adding, “for a little while.”

“And then what?!” inquires

Gyro. “We won’t survive down here

for long… there’s got to be a meter and a half of water between us and

breathable air!”

“And not much sunlight getting

through that water to energize our photosynthetic algae herd,” adds Lyra. “Which means oxygen will soon be in

dwindling supply.”

“What about the starch bodies

they’ve been producing all this time?” I ask. “What will it take to convert it to useable fuel?”

Barron grumbles. “There’s plenty of starch – the little

critters keep cranking it out, but it will have to be desiccated. It’s going to be difficult to remove

all the water without a dehydration chamber for focusing low steady heat and

dry air. And I’m not sure we have

enough fuel remaining to run such a thing…”

Lyra interjects: “Sorry, Barron, I

don’t mean to interrupt… “ she looks around the lab, as if searching for

something undefined. “But… well…

does anyone else hear that?”

For a moment there is silence,

then, as our hearing adjusts to the quietness, a rustling, brushing sound can

be heard coming through the hull.

“Open the crash shutter,” I

suggest, “and let’s have a peek.”

Barron inserts a handle into the

shuttering mechanism and slowly cranks the shutters open.

The porthole reveals the source of

the strange scraping and sliding sounds: a microbe, about the size and shape of

a large watermelon, is pressed against the glass. Beyond the cell, to the limits of sight, tens of thousands –

no, millions, of other similar microbes litter the pond bottom. Some twist and writhe, moving by way of

flagella or finger-like projections, others lie still in layer upon layer of

identical microbes. The world of

the pond bottom is a world swarming with a fantastic diversity of bacteria!

“Well that explains the CO2

levels! “ A glimmer comes to Lyra’s eye.

“Jonathan, “ she begins, but I stop her.

“You most certainly are not going

out there,” I announce firmly. The

others cease their duties and direct their attention to us to see if Lyra is

going to press me with one of her entertaining justifications for going out for

a dip.

“Why in heaven’s name would I want

to do that,” she chides.

“Especially when it’s much easier to bring a bacterium on board for

study!”

1410 hours...

With deft use of a manipulator

claw, capturing one of the plentiful cells was not difficult.

The cell’s shape, oblong, and at

either end a lazily whipping flagellum.

It is now bathing in our examination tray, a large raised rectangular

tub about the size of a large dining table. The bath is filled with pond water and the bacterium is

idling near one end, its flagella occasionally disturbing the surface with a

gentle rippling sound.

Initial observations: The cell appears

much simpler than previously studied microorganisms, such as the ones we have

been tending for oxygen production. Unlike the more complex single cells, the

bacterium has no nucleus, and very few internal organ-elles, just a few fuzzy

bundles inside a gelatin-like cloud.

“But make no mistake,” cautions

Lyra, “there is a lot of chemistry going on in there.”

Another difference from other

single cells is the presence of a semi rigid wall surrounding the bacterium’s

cell membrane: a cell wall, which we theorize serves as a protective shield

from harsh environmental conditions.

“Such protection might allow

bacteria to thrive in some of the most inhospitable places on Earth,” I

conclude.

“Jonathan, look!” cries Lyra. “The examination tray is dissolving!”

To our astonishment the bacterium

appears to have a destructive effect on our examination tub!

“Curious… what is the tray made

of?” I ask.

Lyra considers for a moment, then:

“Plant cell walls, easy to come by and perfect for this application – or so I

thought.”

“We need a closer look,” I say as I

swing a magnifying view lens over the affected area of the try.

“Would you look at that,” whispers

Lyra, peering down through the lens.

“Large molecules appear to be leaving the bacterium through those pores

in the cell wall. Digestive

enzymes, I should think. And

look! The enzymes have a caustic

effect on the tray, breaking it down into smaller subunits – which are absorbed

by the cell. The same process

must be happening outside as well!

Those digestive enzymes must react with dead plants and animals

everywhere down here, reducing them into molecules that the bacterium can use

to build more enzymes, and other molecules of life.”

A harsh scent suddenly stings my

nostrils. “Do you smell that?”

Lyra sniffs at the cabin air. “Jonathan… I’ll bet my grandmother’s

mule that that’s alcohol!”

1500 hours…

Using a low flame of diatom oil, a

coil of copper tubing, and a beaker filled with sample water from around the

bacterium, Lyra has fashioned an effective still. She is about to test the product, a clear fluid in a glass

phial. She inserts a cotton wick

into the phial and sets a burning match to the end. It flares brightly with a clean blue flame… the tell tale

sign of alcohol.

Lyra looks up excitedly. “Well Jonathan, I do believe you are

the luckiest skipper ever commissioned.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Jonathan,” the young naturalist

crows, “our fuel problem is solved!”

2300 Hours…

Working tirelessly into the night,

Barron has been modifying the boiler to burn alcohol, which will allow steam to

generate faster, while requiring substantially less fuel than before. Meanwhile, Lyra, with my assistance,

has collected two-dozen of the fermenting bacteria, and has moved them into

culture tanks where they will convert starch synthesized by our green algae

cells into alcohol. We are

expending the last of our now obsolete oil reserves to fuel lamps set around

the algae pens, so that photosynthesis can kick-start the process. By morning we should have enough pure

distillate to fire up the boiler, work up a head of steam, and resume our

voyage.

At the approach of eight bells, I

retire to my small, corner study and set about organizing the various logs and

journals of the past few days. As

I stow an etching of the captured bacterium and an accompanying diagram of the

chemical process by which we now power the Cyclops,

I reflect on how our new system, a renewable system, so perfectly echoes the

cycles of matter and energy in the living world.

I have come to the inescapable

conclusion that bacteria provide perhaps the most important role in life’s

grand saga. They are the

never-ending recyclers of nutrients – tireless, ubiquitous. These simplest of living things break

down dead organisms, then become food themselves for larger single cells. And those become food for larger organisms

yet. Down here in the shadowy

murk of the bottom ooze, we have discovered a vital link of the food chain.

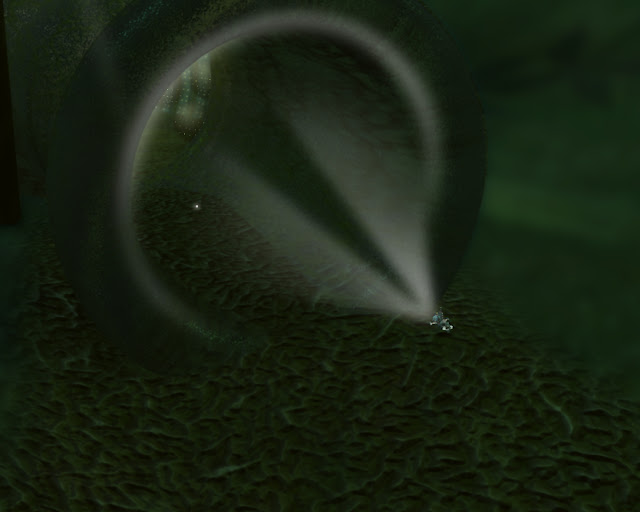

As I gaze out my small porthole

into blackness, lost in the elegance of Earth’s living cycle, a shape

momentarily appears in that encircled frame – but my mind cannot comprehend it,

its form or its very presence, until the shape, a moment later, vanishes from

sight.

It was… though I can scarcely pen

the words… a face.

*****

Author's note: Microscopic Monsters is now being featured on Best Science Fiction Blogs

Comments

Post a Comment