The Age of Discovery, Chapter 19: Faces in the Glass

Day 16: 0800 hours...

“It was your reflection in the porthole,” Barron Wolfe states with a

dismissive certainty that I envy.

“I wish that it had been,” I respond. “Not only did it not look anything like me, it was clearly

outside the ship.”

“How can you be sure?” asks Lyra.

“I mean, maybe your reflection combined with the dim light in the

cabin…”

“Whatever, or whomever it was swatted a flagellating bacterium out of its

way before it vanished back into the dark. No, it was clearly outside. But before it disappeared, it looked straight at me – into me. And its eyes…” I cannot find the words to finish my thought.

“Some microorganism then,” theorizes Barron. “But it couldn’t have been human – not without a helmet or

suit.”

“What about its eyes?” pressed Lyra.

“They were piercing… penetrating…

curious and intelligent,” I tell her. “But not…” And

again, words fail me. “And Barron

is right…eyes, but not human eyes.”

“I’m sorry,” scoffs Lyra. “,but

there are no microorganisms with eyes.

Some have photo-sensitive eyespots, but none have actual eyes that can

look around and see things.

Microorganisms haven’t the nerve complexity to...”

“And yet,” I say softly, my mind tumbling down a trail of possibilities,

“I know what I saw.”

And in the silence that follows I suspect that my crew now considers

their skipper utterly mad.

0815 hours…

“All hands,” came Gyro’s apprehensive tone over the voice pipe, “I’m

getting turbulence on the rudder.

Captain to the pilothouse, please.”

Turbulence on the rudder…

something big and moving nearby.

“Looks like, for now, we have bigger fish to fry,” I declare.

The panes of the observation dome show a smoky green light coming down

from the surface. Outside, the pond

bottom drifts eerily past our windows. Surrounding the Cyclops is a dim world made up of rotting pond plants and

microorganisms. This is the graveyard of the pond – where all pond organisms

fall to rest when life ends. And yet, this is where life begins again – all

thanks to bacteria. And they are everywhere! Some are short rods – others long

ones. Some are even spring-shaped

spirals. Or chains of small round beads. Or hair-like strands! We cannot count

or classify the many species that thrive here on the pond bottom, breaking down

dead organisms and absorbing the all-important chemicals needed for life.

Through the darkness we see larger shapes in the gloom. Predators?

Scavengers?

“Gyro, turn up the driving lamps...” I tell my helmsman. “Perhaps we can catch a glimpse of

whatever is worrying your rudder.”

“Aye, skipper. Lamps to

full.”

As our lights penetrate the gloom, a writhing wall materializes out of

the shadow. Paramecium has arrived,

hordes of them. One after another

the paramecia arrive, establish feeding stations, drawing bacteria into their

oral grooves by the gullet-full. These

large single-celled organisms are feasting on the bottom-dwelling bacteria,

gorging on them as fast as they can – and there are plenty of bacteria to go

around!

1040 hours...

Directly ahead, a throng of paramecia has anchored itself against a mound

of bacteria-rich detritus. The

ciliated protists use their cilia rather ingeniously to hold relatively still

to feed on the bacteria, a situation that affords us an excellent opportunity

to observe the large single-celled organisms up close. Their internal

organelles are easily visible. I

reach for my observation journal and scratch out a short list of first

impressions.

Paramecium

•

Slipper-shaped overall.

•

Outer surface covered with a thick coat of waving cilia.

•

Behavior note: A paramecium uses its cilia in several ways – to move about its

environment both forward and backward, to create a feeding current of water

that draws in food, to hold itself in a “feeding station” where it can easily

suck in large amounts of food organisms.

•

A slot-shaped oral groove that turns

into digestive sacs or vacuoles, filled with captured bacteria. But some parts of bacteria, such as

their cell walls, are not digestible. They must be expelled, but how?

•

A bluish central nucleus. Paramecia appear to have two nucleoli within the nucleus,

differentiating them from most other nucleated cells, which only have a single

nucleolus.

•

A pulsing star-shaped water pump at each end. These contractile

vacuoles work constantly, ridding the cell of excess water entering the

paramecium through osmosis. If it

were not for these pumps, the cell would swell up and burst.

“Skipper,” Gyro says with his now

familiar note of concern, “the parameciums…”

“Paramecia,” corrects Lyra.

“…are closing in around us. “

To underscore Gyro’s concern, the

ship is jostled lightly, then more forcefully, as individual paramecia brush

against the hull, an ongoing contest for the best feeding spots.

“Individually there isn’t much

damage they can do to the ship,” says Lyra, then adding, “but they are the size

of orca whales – to us anyway. A

large number of them might cause some damage. Maybe it would be prudent to move on.”

I can scarcely believe that these

words of caution are coming from my usually reckless naturalist.

“A sensible suggestion,” I

agree. “Gyro, watch for a gap in

the paramecia. When one appears,

take us through it.”

We find ourselves beneath a dome of

writhing, contorting oblong shapes, fluidly pushing their way deeper into the

detritus mound, competing for the richest bacterial mines.

After several moments of

observation, Lyra turns her back on the external view. “Jonathan, some of these bacteria may

be light sensitive,” she announces.

“I believe they are drawn to the ship’s lamps. And that, in turn, is attracting more of the paramecia.”

“That would explain why there seems

to be more and more of these… paramecia,”

says Gyro with razor-sharp diction, and a wink in my direction.

I give the order to douse the

driving lamps, and to reduce the Edison current to half illumination. Darkness fills the observation

panes.

“That’s doing it,” reports Lyra

after a short time. “Bacteria

activity is slowing down a bit.

Less activity should equate to less bacterial metabolism. Emphasis on should…”

“It’s working,” announces Gyro,

visibly straining to see through the dim murk. “I think there’s a gap opening up at one o’clock.”

“Finally,” I say softly. “Make for it, Gyro – double slow.”

“Answering double slow,” says Gyro

as he rings the engine order telegraph.

Cyclops

inches forward, her bow aimed for an irregular void in the otherwise

impenetrable wall of paramecia.

The gap reveals nothing on the other side but blackness. We steam ever so slowly toward that opening. The perimeter of the opening shifts

constantly as paramecia jockey for the best feeding stations, but I am

encouraged to see that with each passing moment the gap remains large enough to

accommodate Cyclops.

“When we enter the gap,” I tell

Gyro, “turn the driving lamps back up.

I want to see where we are going.”

“Aye, Skipper,” answers Gyro. “Heading into the gap… now.”

The edges of the opening, alive

with feeding, contorting, whale-sized protozoa, move slowly past the

observation panes. We are

tiptoeing through the lion’s den, shielded by our science – the sightless

organisms do not detect CO2-free Cyclops.

“We are almost through the gap,”

reports Gyro.

“Good,” I respond. “Then let’s

crank up the lamps.”

As we leave the living threshold,

Gyro turns the control and sends more Edison current to the driving lamps.

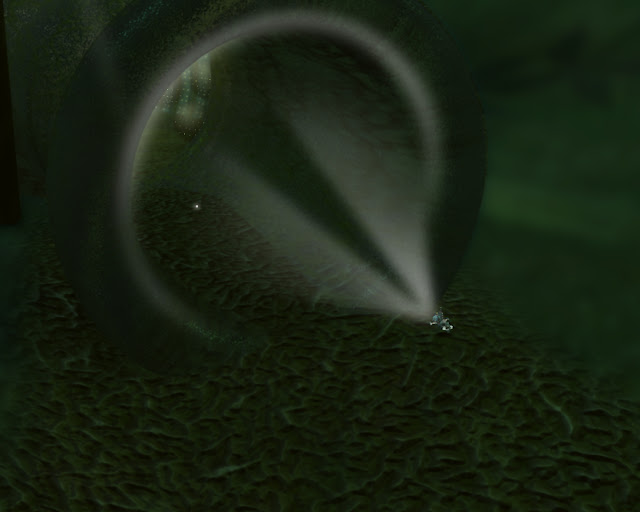

“What in the name of Neptune…”

shouts Lyra, staring straight ahead, shielding her eyes.

I cannot make sense of what I am

seeing. Brilliant lights are

shining back at us, filling the pilothouse with warm illumination. But how?

“It’s glass,” says Gyro,

laughing. “And those are our own

lamps being reflected back at us!”

To illustrate his conclusion, Gyro

fades the lamps down, then up again.

The lights shining back at us are indeed our own. But as I look at the reflection I see

something else set behind that glass, and words catch in my throat. I take a few steps forward, to the

front of the pilothouse. I reach

out and touch the glass of our own observation dome, now less than a quarter

millimeter from the mysterious reflective surface beyond. There, behind that larger wall of glass

are faces. Many faces.

“Do… do you see them?” I stammer to

whomever is listening.

Barron arrives in the pilothouse,

but is moved to silence. There is

a long moment of timelessness, an eternity thunderous with the sound of

nothing. Then finally, Lyra steps

up to my side and places her hand on my shoulder.

“Yes, Jonathan.” Her voice is hushed, both convinced and

disbelieving at the same time. “We all see them, too.”

*****

Author's note: Microscopic Monsters is now being featured on Best Science Fiction Blogs

Comments

Post a Comment